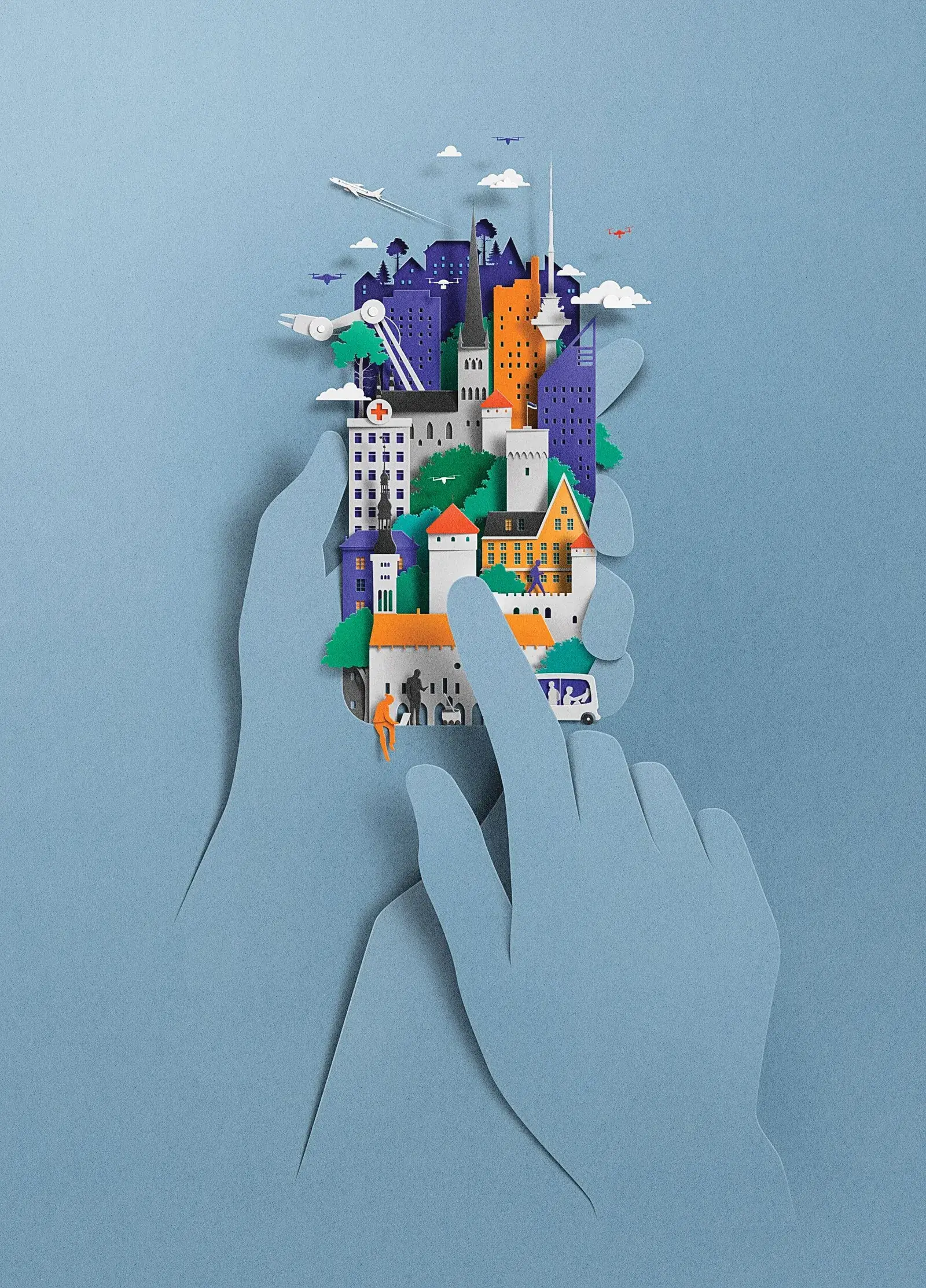

Estonia, the Digital Republic

Its government is virtual, borderless, blockchained, and secure. Has this tiny post-Soviet nation found the way of the future?

By Nathan Heller

The Estonian government is so eager to take on big problems that many ambitious techies leave the private sector to join it. Illustration by Eiko Ojala

Up the Estonian coast, a five-lane highway bends with the path of the sea, then breaks inland, leaving cars to follow a thin road toward the houses at the water’s edge. There is a gated community here, but it is not the usual kind. The gate is low—a picket fence—as if to prevent the dunes from riding up into the street. The entrance is blocked by a railroad-crossing arm, not so much to keep out strangers as to make sure they come with intent. Beyond the gate, there is a schoolhouse, and a few homes line a narrow drive. From Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, you arrive dazed: trees trace the highway, and the cars go fast, as if to get in front of something that no one can see.

Within this gated community lives a man, his family, and one vision of the future. Taavi Kotka, who spent four years as Estonia’s chief information officer, is one of the leading public faces of a project known as e-Estonia: a coördinated governmental effort to transform the country from a state into a digital society.

E-Estonia is the most ambitious project in technological statecraft today, for it includes all members of the government, and alters citizens’ daily lives. The normal services that government is involved with—legislation, voting, education, justice, health care, banking, taxes, policing, and so on—have been digitally linked across one platform, wiring up the nation. A lawn outside Kotka’s large house was being trimmed by a small robot, wheeling itself forward and nibbling the grass.

“Everything here is robots,” Kotka said. “Robots here, robots there.” He sometimes felt that the lawnmower had a soul. “At parties, it gets close to people,” he explained.

A curious wind was sucking in a thick fog from the water, and Kotka led me inside. His study was cluttered, with a long table bearing a chessboard and a bowl of foil-wrapped wafer chocolates (a mark of hospitality at Estonian meetings). A four-masted model ship was perched near the window; in the corner was a pile of robot toys.

“We had to set a goal that resonates, large enough for the society to believe in,” Kotka went on.

He is tall with thin blond hair that, kept shaggy, almost conceals its recession. He has the liberated confidence, tinged with irony, of a cardplayer who has won a lot of hands and can afford to lose some chips.

It was during Kotka’s tenure that the e-Estonian goal reached its fruition. Today, citizens can vote from their laptops and challenge parking tickets from home. They do so through the “once only” policy, which dictates that no single piece of information should be entered twice. Instead of having to “prepare” a loan application, applicants have their data—income, debt, savings—pulled from elsewhere in the system. There’s nothing to fill out in doctors’ waiting rooms, because physicians can access their patients’ medical histories. Estonia’s system is keyed to a chip-I.D. card that reduces typically onerous, integrative processes—such as doing taxes—to quick work. “If a couple in love would like to marry, they still have to visit the government location and express their will,” Andrus Kaarelson, a director at the Estonian Information Systems Authority, says. But, apart from transfers of physical property, such as buying a house, all bureaucratic processes can be done online.

Estonia is a Baltic country of 1.3 million people and four million hectares, half of which is forest. Its government presents this digitization as a cost-saving efficiency and an equalizing force. Digitizing processes reportedly saves the state two per cent of its G.D.P. a year in salaries and expenses. Since that’s the same amount it pays to meet the nato threshold for protection (Estonia—which has a notably vexed relationship with Russia—has a comparatively small military), its former President Toomas Hendrik Ilves liked to joke that the country got its national security for free.

Other benefits have followed. “If everything is digital, and location-independent, you can run a borderless country,” Kotka said. In 2014, the government launched a digital “residency” program, which allows logged-in foreigners to partake of some Estonian services, such as banking, as if they were living in the country. Other measures encourage international startups to put down virtual roots; Estonia has the lowest business-tax rates in the European Union, and has become known for liberal regulations around tech research. It is legal to test Level 3 driverless cars (in which a human driver can take control) on all Estonian roads, and the country is planning ahead for Level 5 (cars that take off on their own). “We believe that innovation happens anyway,” Viljar Lubi, Estonia’s deputy secretary for economic development, says. “If we close ourselves off, the innovation happens somewhere else.”

Read the Full Article.