Suriname to offer creditors oil-linked bonds

ESG opportunity in restructuring

Part I

globalcapital / eyesonsuriname

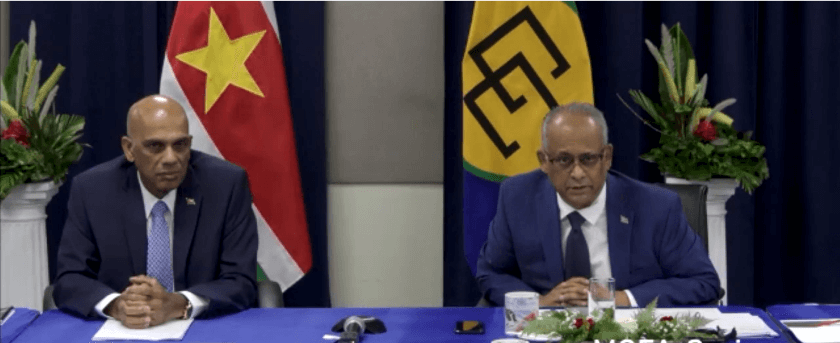

Amsterdam, February 15th 2022== Suriname’s debt workout has the ingredients to be a fascinating case study for sovereign restructuring. GlobalCapital spoke exclusively to the two ministers leading creditor negotiations, Armand Achaibersing (l) and Albert Ramdin (r).

Suriname is only just pulling out of a deep recession, and Chandrikapersad Santokhi’s government faced little choice but to begin restructuring the country’s vast debt burden when elected in July 2020. The government — having received IMF Executive Board Approval for its Extended Fund Facility in December — said in a creditor update this week that it wants to wrap up the restructuring by March.

Though it only involves two international bonds, Suriname’s debt restructuring process could bring lessons for the world.

First, recent offshore oil findings have the potential to transform the economy, and lie tantalisingly on the horizon. Naturally, bondholders want this to be reflected in economic projections, but oil revenues are not likely to materialise until 2025 or 2026 at the earliest, meaning creativity will be required.

Meanwhile, Suriname is attempting to apply principles of intercreditor equity — as extolled by the G20 Common Framework for debt treatment — and balance the interests of official and private creditors, but is not eligible for the framework, despite its major recent economic woes.

Finally, while the bond market craze for ESG debt shows no sign of slowing, can Suriname use its credentials as one of a tiny minority of carbon-b=negative countries?

Shortly before they presented their latest credito update, the two ministers leading Suriname’s restructuring negotiations shared their views with GlobalCapital on value recovery mechanisms, international debt restructuring architecture, the potential to incorporate ESG, and the next challenges facing the smallest country in South America.

The road to recovery

When President Santokhi took office just months into the Covid-19 pandemic, he faced quite the task.

Not only did he have to procure the computers that had gone missing when his predecessor Desi Bouterse left office, but Santokhi inherited a country heavily reliant on monetary financing, a spiralling black market exchange rate, dwindling international reserves, and a government debt ratio nearing 150% of GDP.

Santokhi recruited Armand Achaibersing, chairman of the Surinamese Association of Insurance Companies, as minister of finance and planning. Albert Ramdin, a former assistant secretary general of the Organization of American States (OAS) who had been a senior director at Newmont Mining since 2016, joined the cabinet as minister of foreign affairs, international business and international co-operation. There followed several measures looking to rebalance the economy, including unifying the parallel exchange rates, increasing energy tariffs and taxes, and prioritising spending to reign in the budget deficit.

Alongside all these reforms, however, came a crucial step: renegotiating Suriname’s crippling debt, including its $550m 2026 bonds and a $125m 2023 note. The authorities hired Lazard as a financial advisor and White & Case as a legal advisor.

Initially, negotiations with bondholders appeared to be going smoothly, as the government followed an approach — successfully used by Ecuador earlier in 2020 — of asking for consensual payment standstills that would give it time to restructure without entering hard default. Suriname’s bondholders approved two consent solicitations — in November 2020 and April 2021 — giving the government enough time to clinch a staff-level agreement with the IMF on an Extended Fund Facility.

However, relations appeared to turn sour after the government outlined its first restructuring offer to bondholders in June 2021, with the creditor committee — led by Franklin Templeton, Eaton Vance, GMO and Greylock and advised by Newstate Partners and Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe — arguing that the offer was “well outside the bounds of good faith negotiations”. The proposed haircut was far larger than most had expected, and the lack of consideration of oil discoveries in the macroeconomic framework was a clear sticking point. In response, Suriname called the bondholders’ stance “unconstructive and confrontational”.

Moreover, Suriname had to wait an unusually long time for its IMF deal; it was late December by the time the Fund’s Executive Board finally approved the programme. But the stage is now set for further negotiations.

End Part I

Proceed to Part II

Global Capital