China Buys Influence in Western Press

Part IV

louisalim/guardian/eyesonsuriname

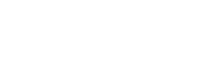

Amsterdam, June 30th 2022– The use of foreign radio stations to deliver government-approved content is a strategy the CRI president has called jie chuan chu hai, “borrowing a boat to go out to the ocean”. In 2015, Reuters reported that Global CAMG was one of three companies running a covert network of 33 radio stations broadcasting CRI content in 14 countries. Three years on, those networks – including Ostar – now operate 58 stations in 35 countries, according to information from their websites.

In the US alone, CRI content is broadcast by more than 30 outlets, according to a combative recent speech by former US vice president, Mike Pence, though it’s difficult to know who is listening or how much influence this content really has.

Beijing has also taken a similar “borrowed boats” approach to print publications. The state-run English-language newspaper China Daily has struck deals with at least 30 foreign newspapers – including the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post and the UK Telegraph – to carry four- or eight-page inserts called China Watch, which can appear as often as monthly.

The supplements take a didactic, old-school approach to propaganda; recent headlines include “Tibet has seen 40 years of shining success”, “Xi unveils opening-up measures” and – least surprisingly of all – “Xi praises Communist party of China members.”

Figures are hard to come by, but according to one report, the Daily Telegraph is paid £750,000 annually to carry the China Watch insert once a month. Even the Daily Mail has an agreement with the government’s Chinese-language mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, which provides China-themed clickbait such as tales of bridesmaids on fatal drinking sprees and a young mother who sold her toddler to human traffickers to buy cosmetics. Such content-sharing deals are one factor behind China Daily’s astonishing expenditures in the US; it has spent $20.8m on US influence since 2017, making it the highest registered spender that is not a foreign government.

The purpose of this “borrowed boats” strategy may also be to lend credibility to the content, since it’s not clear how many readers actually bother to open these turgid, propaganda-heavy supplements. “Part of it really is about legitimation,” argues Peter Mattis. “If it’s appearing in the Washington Post, if it’s appearing in a number of other papers worldwide, then in a sense it’s giving credibility to those views.”

In September, Donald Trump criticised this practice, claiming China was pushing “false messages” intended to damage his prospects in the midterm elections. His wrath was directed at a China Watch supplement in the Iowa-based Des Moines Register, designed to undermine farm-country support for a trade war. He tweeted: “China is actually placing propaganda ads in the Des Moines Register and other papers, made to look like news. That’s because we are beating them on Trade, opening markets, and the farmers will make a fortune when this is over!”

In the Xi Jinping era, propaganda has become a business. In a 2014 speech, propaganda tsar Liu Qibao endorsed this approach, stating that other countries have successfully used market forces to export their cultural products. The push to monetise propaganda provides canny businesspeople with opportunities to curry favour at high levels, either through partnering with state-run media companies or bankrolling Chinese proxies overseas. The favoured strategy now is not just “borrowing foreign boats” but buying them outright, as the University of Canterbury’s Anne-Marie Brady has written.

The most visible example of this came in 2015, when China’s richest man acquired the South China Morning Post (SCMP), a 115-year-old Hong Kong paper once known for its editorial independence and tough reporting. Jack Ma, whose Alibaba e-commerce empire is valued at $420bn, has not denied suggestions that he was asked by mainland authorities to make the purchase.

“If I had to bother about what other people speculated about, how would I get anything done?” he said in December 2015. Around the same time, Alibaba’s executive vice-chairman Joseph Tsai made clear that under new ownership, the SCMP would provide an alternative view of China to the one found in western media: “A lot of journalists working with these western media organisations may not agree with the system of governance in China and that taints their view of coverage. We see things differently, we believe things should be presented as they are,” Tsai told an interviewer.

End Part IV

Part V follows

louisalim/guardian/eyesonsuriname