The Oil Curse

Stark Warning Guyana President

Goes for Suriname as well

Financial Times/ eyesonsuriname

Amsterdam, May 4th 2022–The president of Guyana, the world’s fastest-growing economy, is inviting investors to back his ambitious vision to transform the small South American country into a regional health, education and transport hub with the help of burgeoning oil wealth.

We’re investing tremendously in healthcare. and we’re investing heavily in education”, President Irfaan Ali, 42, told the Financial Times in an interview while visiting London last week to seek investment.

But not only are we investing in healthcare and education to fulfil the needs of Guyanese, we’re investing in healthcare and education as important foreign currency earners of the future . . . so Guyana can become a health and education hub for South America, for the Caribbean and the huge diaspora that resides in North America.”

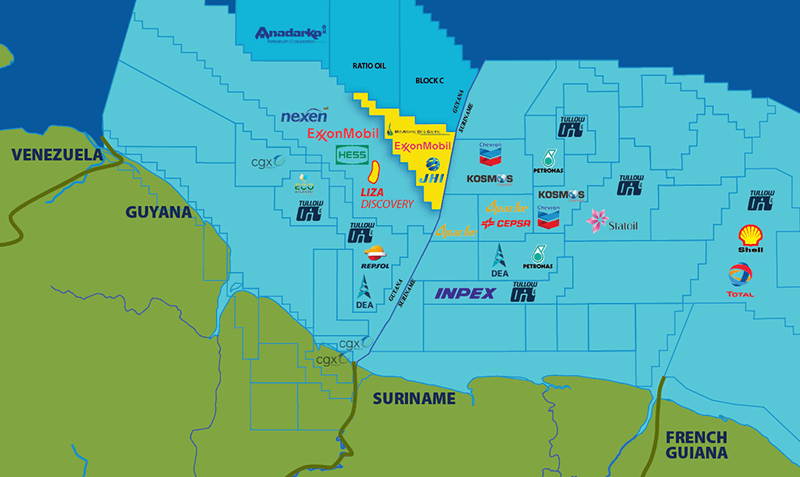

A former British colony with a population of 787,000, Guyana’s fortunes have changed out of all recognition since ExxonMobil discovered large offshore oil deposits in 2015. Crude oil production began in 2019 and is rising rapidly. Exxon and its partners, Hess and China’s Cnooc, plan to reach output of 340,000 barrels per day this year. Ali said Guyana’s oil production could exceed 1mn b/d in three years, increasing revenue for the government of almost $4bn this year to $10bn a year from 2025. Until recently one of the poorest countries in the Americas, Guyana is hoping to avoid the “oil curse” that has befallen so many nations by spending its newfound wealth on building a sustainable economy for the long term.

Transport infrastructure is a crucial element. South America’s only English-speaking country, Guyana has historically been cut off from its neighbours by rivers and jungle, but the government is planning to build highways and bridges connecting it to French Guiana and Suriname to the east and Brazil to the south. These road links, plus a planned deep water port on its Caribbean coast, could open up a transport corridor from northern Brazil to Atlantic markets. “We have intense discussions going on with Abu Dhabi Ports . . . about the development of a major deepwater harbour in Guyana,” Ali said. “That deepwater harbour will support northern Brazil and give them access to the Atlantic.” Ali estimated the likely cost of the port as “on the upside of $2bn”. He said Abu Dhabi Ports was offering to finance the project but the Guyanese government might co-invest.

For a highway going south to Brazil, Ali said a tender for construction of the first section had already been awarded and work would begin soon.

As its oil industry develops, Guyana is considering creating a national oil company. But Ali stressed that if this were to happen, it would “operate like a business” and would focus on new development and “never ever be part of taking over existing production from foreign operators. That is out of the question,” he said. The rapid rise in oil production means Guyana’s economy is forecast to grow 47 per cent this year, the fastest in the world, according to the IMF.

This comes on top of growth of 20 per cent last year and 43 per cent the year before. A sovereign wealth fund has been created to safeguard the oil revenues for future generations. We’re not in the business of building fanciful infrastructure. We have to build infrastructure that the country needs Irfaan Ali, president of Guyana David Jessop, editor of Caribbean Insight and an expert on Guyana, said the biggest constraint to Ali’s ambitions was likely to be a lack of people.

When you look at the size of Guyana’s population and where it is located, you realise that the main constraint is human resources,” he said. “The country’s potential is there but to deliver it is a real serious challenge.”

Ali is keen to emphasise other assets which existed before oil was discovered, such as Guyana’s 18.5mn hectares of rainforest, which could support eco-tourism and a biodiversity centre as well as generating revenue from conservation.

Many people don’t know that Guyana’s forests store 19.5 gigatonnes of carbon,” he said. “That can have an annualised income of close to $200mn through carbon credits and carbon markets.”

Ali said the oil boom had brought visits from a wide array of international financial institutions, sovereign wealth funds and investment funds. Other actors with less benevolent intentions have also taken an interest. Venezuela has stepped up pressure over its longstanding territorial claim — which dates back to the 19th century — to the western two-thirds of Guyana. Guyana has referred the dispute to the International Court of Justice and Ali said: “We have been consistently encouraging Venezuela to participate fully in the process and to respect the outcome of the ICJ.”

The road to Brazil could also prove a double-edged sword, bringing not only valuable cargo traffic to a new Guyanese port but also a potential influx of loggers, land grabbers and wildcat miners from Brazilian frontier areas. Policing such large swaths of virtually uninhabited rainforest is likely to prove a significant challenge for Guyana’s police and armed forces, given the country’s population. The hurdles to the achievement of Ali’s vision are formidable.

Many developing countries have squandered oil wealth in corruption, wasteful construction projects and shortlived consumption booms. There may also be political issues. Guyana’s democracy is fragile and the country has long been divided along ethnic lines between the majority Afro-Guyanese and the minority Indo-Guyanese.

Ali belongs to the latter group and his election victory in 2020 led to a tense stand-off lasting months before incumbent David Granger accepted the result. When asked about the challenges ahead, the Guyanese president tried to strike a cautionary note. “As a people, we have to remain humble,” Ali said. “We’re not in the business of building fanciful infrastructure. We have to build infrastructure that the country needs . . . and not investment in infrastructure that looks good.”

eyesonsuriname / Financial Times