Warning from Latin America

Economic stagnation, popular frustration and polarization

eyesonsuriname

Amsterdam, June 19th 2022–

When they vote in a presidential run-off election this weekend [ June 18/19th 2022 ] Colombians face a difficult choice between two ill-qualified populists.

The choice between presidential candidates in Colombia has become worryingly familiar in all of Latin and South American elections.

On the left, Gustavo Petro is still sympathetic towards and delirious over Hugo Chávez, responsible for destroying Venezuela’s economy and its democracy.

On the right, Rodolfo Hernández, a former mayor with no team and no real program.

This line-up reflects voters’ deep scorn for Colombia’s mainstream politicians, even though the country has done relatively well over the past 20 years.

There seems no longer room for the moderation, compromise and gradual reform needed to become prosperous and peaceful.

That matters not just to Latin America, but to the rest of world. Despite everything, the region remains largely democratic and should be a natural ally of the West. Complementing the efforts in Eastern Europe, the Balkan and Baltic countries to fall again under the spell and terror of those who dominated those parts of the Europe far too long.

Latin America can play a vital role, too, in helping solve other global problems, from climate change to food security as well as the struggle to keep the world safe from autocratic thugs and those who want to forcefully impose their non-functional social and financial systems to silence the voices for freedom and equality.

It is home not only to the fast-diminishing rainforest in the eight Amazon countries and much of the world’s fresh water but also to a wealth of commodities needed for green energy, such as lithium and copper. It is a big food exporter and could provide more.

Not so long ago, Latin America was on a roll. A commodity boom brought healthy economic growth and provided politicians with the money to experiment with innovative social policies, such as conditional cash-transfer programs. That, in turn, helped bring about big falls in poverty, reducing the extreme income inequality and differences long associated with the otherwise attractive region.

The middle classes grew.

That helped establishing political stability. Democratic governments generally tried to respect human rights, even with weak rule of law. Growing prosperity and more responsive and effective politicians appeared to be reinforcing one another.

The future was bright. No longer.

Now that virtuous circle has been replaced by a vicious one. Latin America is stuck in a worrying development trap. Its economies have suffered a decade of stagnation or slow growth. Its people, especially the young, who are more educated than their parents, have become frustrated by their lack of opportunity. They have turned this anger against their politicians, who are widely seen as corrupt and self-serving. The politicians, for their part, have been unable to agree on the reforms needed to make Latin America’s economies more efficient. The productivity gap with the more developed countries has widened since the 1980s.

With too many monopolies and not enough innovation, Latin America is falling short in the 21st-century economy.

These challenges are becoming more acute. The impact of the pandemic, especially very long school- and other educational institutes closures, increases inequality. Governments need to spend more on health care and education, but the cost of servicing debt is rising. The region thus needs to raise more tax, but in ways that do not undermine investment.

The consolidation of democracy used to be seen as a one-way street. But Latin America shows that democracies can easily fall apart and that is a warning for democratic movements everywhere. Its politics are now marked not just by polarization, but also by fragmentation and making stable governing majorities hard to assemble. (see Bello).

This downward spiral is accelerated by the malign influence of social media, trolls from Russia and the import of identity politics from the north. Technocrats are discredited and jobs in government are increasingly seen, on both the left and the right, as perks to be doled out rather than crucial responsibilities to be reserved for capable administrators. Organized crime, with imprisoned Brazilian gangs, already a huge factor in the region’s epidemic of violence, is starting to taint its politics, too. Not only drug smuggling but cooperation with terrorist organizations like Hezbolla and with the Calabrian mafia, make those gangs more powerful than well known, established multinational and global firms. Financing of illegal gold mines in neighbouring countries like Suriname, contaminating rivers with mercury and thus poisoning the local people.

Human trafficking, money laundering, it is all in their books. The influence on neigbouring countries of these imprisoned gangs in Brazil is yet another crisis Europe can ill afford on top of the crises we already have to address. Since it is through these neigbouring countries narcotics are smuggled and via the ports of Rotterdam, Hamburg and Antwerp reach their destination in Europe, where our democratic institutions are further destabilized.

Many of these are ills of the democratic world in general, but they are particularly acute and dangerous in Latin America.

Most Latin Americans still want democracy, albeit a much better version than they have. But there is a growing audience for those advocating the supposedly effective hand of autocracy. Venezuela and Nicaragua have become left-wing dictatorships like Cuba. In El Salvador, Nayib Bukele has centralised power and locked up some 40,000 people in a draconian war on gangs. He is the region’s most popular president. The leaders of its two biggest countries, Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil and Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico, are contemptuous of checks and balances. Mr. Bolsonaro will seek a second term at an election in October.

He is likely to lose to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a former president whose governments were linked to corruption and who lacks new ideas.

The risk is not just that democracies devolve into dictatorships, but that Latin America drifts away from the spheres of Europe. In much of the region, China is now the main trade partner and is investing in infrastructure. Some of the region’s left-wing governments seem keen to return to the non-alignment of the cold-war era.

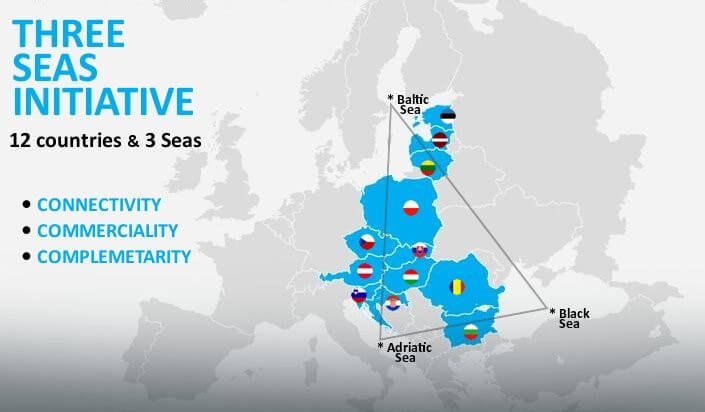

Five of the region’s presidents, including Mr López Obrador, chose to boycott this month’s Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles. Europe could do much more to engage Latin America, through trade, investment and technology. But Latin America in turn needs to recognise that it has much to gain from rebuilding closer ties, and that its role in a world dominated by China would be that of a neo-colony. Perhaps the 3 seas initiative could be an example.

The temptation in the region will be to ignore the economic and political malaise and simply surf the new commodity boom triggered by the war in Ukraine. That would be a mistake.

There is no easy way out and there are no short cuts.

Latin Americans need to rebuild their democracies from the ground up. If the region does not rediscover a vocation for politics as a public service and relearn the habit of forging a consensus, its fate will get only worse.

eyesonsuriname